Another holiday season has come to 52nd Street and efforts are continuing to help the teeming commercial strip regain its reputation as “West Philly’s Main Street.”

Over the past five years, the Enterprise Center’s Community Development Corporation (TEC-CDC) has invested in the renewal of 52nd Street, a once busy commercial corridor hit hard by the 10-year Market-Frankford EL reconstruction project. Providing guidance and support, the neighborhood initiative group has worked to spur economic growth in the area, hoping to bring back its vitality.

As part of those efforts, TEC-CDC recently hired Akeem Dixon as the retail gateway’s first-ever Commercial Corridor Manager, made possible by support from the Philadelphia Local Initiative Support Corporation (LISC). In his role, Dixon will primarily oversee a cleaning contract managed by the center, funded in part by the Philadelphia Department of Commerce, aimed to “help make 52nd Street the best it can be,” said Bryan Fenstermaker, TEC-CDC’s senior director of programming.

“Our [work] is to make 52nd Street the most attractive and vibrant corridor that it can be,” Fenstermaker told West Philly Local. “52nd Street is really the livelihood of West Philadelphia … A number of people grew up here on the corridor and remember what it used to be like. There’s no reason it can’t come back.”

Hiring a portal manager is a major development not only for the corridor, but for the local organization, which has a hand in its planning and economic growth. According to Fenstermaker, the new manager will also serve as a soundboard for the “wants and needs” of the area, helping TEC-CDC leverage the requests of 52nd Street’s businesses and residents. Dixon will, in effect, act as a liaison for those partners involved in the corridor—be they local community associations or business owners and street vendors—so there’s full engagement among everyone who has a stake in 52nd Street’s success.

“What we would like to see is the businesses and vendors come together to support somebody that’s full-time on there as a sustainable practice,” said Fenstermaker. “We’re there to support the stakeholders and the corridor, so I see us being there long-term.”

Old Glory Days

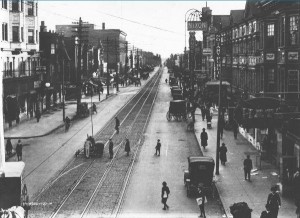

Decades ago, 52nd Street was once West Philadelphia’s epicenter for entertainment and shopping. Along the path between Arch Street and Baltimore Avenue stood indulgent eateries, upscale boutiques, upstart financial institutions, and bustling cinemas that served the vibrant residents of the quilted neighborhood. Affectionately known as “The Strip,” 52nd Street was West Philly’s Main Street—an epithet forever marked by a street medallion.

Over the last 30 years, though, the enthusiasm that once filled 52nd Street’s air has died down to a whisper. Locals were taking their dollars to shop on the outskirts of Philadelphia proper, if they didn’t leave the area all together. Companies couldn’t sustain their livelihood with the lack of profit—and interest—shuttering its doors for good. Once hallmarks for West Philly’s lifeline, almost century-old buildings were even torn down. Erected in 1910, the Nixon Theatre, a 1,870-seat vaudeville theater-turned-thriving soul spot, closed in 1984, only to be demolished a year later.

It was a descent exacerbated by the El reconstruction, started in 2000. For 10 years, SEPTA’s $750 million dollar project uprooted the rail line between 46th and 69th Streets, interrupting transit service and street traffic. According to Plan Philly, a total of 47 businesses closed in that time, causing “massive disruption” to a corridor shadowed by one of the MFL’s busiest stops.

But, in 2008, city officials and local organizations joined forces for the 52nd Street Partnership Network to launch a multimillion revitalization effort in hopes of bringing back the Strip’s glory days—or, at least, develop new ones. It’s a large and well-established group: U.S. Representative Chaka Fattah and Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell are both heavily invested in the project, as much of West Philadelphia is in Blackwell’s third district and Fattah’s second district. Other members of the network include the 52nd Street Business Association, TEC-CDC, the 52nd Street Community Development Corporation, the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians, and the Commerce Department, which funds a number of the project’s initiatives.

“[52nd Street] is a very important commercial corridor not only to West Philadelphia, but the city itself,” said Aiisha Herring-Miller, senior manager of the Commerce Department’s Philadelphia Empowerment Zone & Neighborhoods. “With all that activity, it was a no-brainer for why we should be out there.”

So far, those efforts have paid off. Businesses are starting to crop up again along the stretch between Arch and Walnut Streets. Payless ShoeSource and Rainbow Kids now stand where the Nixon used to be. Food markets, hair and nail salons, convenience stores, and beauty shops are settling into vacant space, few of which exist now according to Herring-Miller. And, a mainstay of the Strip for 100 years, street vendors continue to line up on the pavement with their merchandise for sale.

This holiday season, TEC-CDC is encouraging West Philly residents to shop at those businesses, like The Art of Beauty Salon (135 South 52nd Street), Hakim’s Bookstore & Gift Shop (210 South 52nd Street), Shirt Happens (212 South 52nd Street), Babe (110 South 52nd Street), and Urban Art Gallery (262 South 52nd Street). As part of its #ShopWestPhilly campaign, locals could win a $50 gift certificate for tweeting a picture with the hashtag of their shopping or dining excursion in the corridor (and West Philly at large).

Part of a Bigger Picture

But, as the cleaning initiative shows, refreshing 52nd Street is not only a matter of sustaining established businesses and attracting new ones — like a hardware store and sit-down restaurants, still currently missing from the Strip. It’s also about transforming 52nd Street into the safe and aesthetically pleasing pathway it once was for the benefit of the community—something Herring-Miller said residents have expressed they would like.

“You can’t develop a healthy corridor if it’s not clean and it’s not safe,” Fenstermaker said.

Much of this mission is embedded in the 52nd Street Economic Development Plan, commissioned in 2010 and done in partnership with Councilwoman Blackwell and the City Planning Commission. As part of this plan, partners involved in the corridor project are implementing a slew of actions to improve West Philly’s Main Street, including TEC-CDC’s cleaning efforts. Twenty-one eligible business owners were also able to revamp their storefronts through reimbursements offered through the Storefront Improvement Program, which launched in 2011 with help of a nearly $300,000 federally-funded grant secured by Rep. Fattah. The program’s end results, unveiled last year, include new colorful facades, entryways, windows, exterior lining, and signage, among other updates.

“If a business is appealing from the eye, it could increase their foot traffic, and hopefully their revenue,” Herring-Miller told West Philly Local.

The Commerce Department will also help fund the corridor’s next big development: a Vendors Program run by the Welcoming Center for New Pennsylvanians that will provide education and technical assistance to street merchandisers through various workshops. At the end of the program, successful vendors will receive a new mobile cart to sell their wares from, the production of which is overseen by the Welcoming Center. According to Fenstermaker, the updated merchandising unit is meant to uniform the look among the vendors, solidifying the new brand of 52nd Street.

Striking a Balance

This progress hasn’t been easy to achieve, though.

In 2009, a year after the partnership network formed, the city set into motion plans to remove the canopies erected in 1976. Those canopies, built by Philadelphia Commercial Development with the support of Blackwell’s late husband, Lucien (who served the third district from 1974 to 1991), were meant to provide coverage for vendors and shoppers from bad weather and, as Philadelphia Weekly reported, “to create a more comfortable, successful business environment.”

But, much like the businesses that slowly went away, the canopies from Arch to Walnut Streets started deteriorating to the point of disrepair. To the city, they became a safety hazard, costing far more to restore than to take down, according to Plan Philly. To vendors, though, it was a sign of gentrification—the first step in stripping 52nd Street of the character that’s developed and thrived there.

“They take down the canopies because they know the vendors and the shoppers ain’t gonna come out when it snows, sleets and rains, and they know we gotta be out here every day to survive. They make us disappear, they hope, and then all the construction disrupts business and the stores go broke … Then you get Starbucks, FedEx, these big corporations comin’ in that make the city some real money, the real-estate developers comin’ in, and pretty soon we’re forced out of the neighborhood,” Bashir Postley, a 52nd Street vendor, told Philadelphia Weekly in 2011.

Vendors’ suspicions of the removal were palpable, so much so that they organized a protest in 2009, with some chaining themselves to canopy poles. In response, the city put the project on hiatus, returning to the drawing board and, this time, actively engaging vendors in the process. Two years later, the damaged awnings were gone.

Even so, the worry that upscale businesses like Starbucks and H&M will overrun 52nd Street is still real. It’s the byproduct of any commercial revitalization program. Just look at 125th Street in Harlem, New York. Once chock full of bodegas and small, local businesses, the shopping avenue is now an ode to big chain box stores like Marshals.

“That’s something I don’t want to happen to 52nd Street,” said Herring-Miller, whose family is from Harlem, and who saw the transformation first-hand.

What she does want, though, is to strike a balance—to give residents the business they want to see in their neighborhood, while bringing in the businesses they may also need. As for a Starbucks planting its flag on 52nd Street, she doesn’t anticipate that happening anytime soon—although, as neighborhoods go through “certain changes,” it very well good in 10 years, she admits. But, for right now, it’s about being respectful of businesses, vendors, and the community, and their needs.

“It’s a fine line that you really have to walk with doing the link with neighborhood economic development,” she told West Philly Local. “It’s a balance.”

–Annamarya Scaccia

CORRECTION, December 11, 3:30 p.m.: An earlier version of this article included a misspelling of Bryan Fenstermaker’s name. It is Fenstermaker, not Fenstermacher. Additionally, it had listed TEC-CDC as a University of Pennsylvania-affiliated organization. While TEC-CDC was founded by UPenn, it has not been affiliated with the institution for over a decade. We regret the errors.

December 11th, 2013 at 10:22 am

What about the commercial corridor of 52nd street north to Girard?

December 17th, 2013 at 2:10 pm

Hi Robin,

Right now, the Commerce Department is focusing on 52nd Street between Arch and Walnut. I believe there are plans to go further in the future, but I wasn’t given specifics.