Happiness. That’s a hard thing to think about. I think there is some moment in time when childhood simplicity slips away and the American “happy chase” takes over. And it is a race unto the death.

Americans are obsessed with happiness. Parents claim that all they want is for their children to be happy. Adolescents pine away for the guy or the girl or thing or the status that will make them happy. College students turn to their shrinks for answers, asking, “Why can’t I just be happy?” But how often do we take the chance to stop, look inside ourselves, and truly ask, am I happy? How often do we ask not what people are doing with their lives, but how they feel doing it? What is happiness and what really makes us happy? How do we control our happiness? And how does society shape the way we envision happiness? These are the questions The Happy Show, a current exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Art (36th & Sansom), asks its visitors.

Walking through The Happy Show is like walking through the inside of a brain, designer Stefan Sagmeister’s brain. Small tidbits of handwritten commentary and parenthetical thought bubbles are sketched across the physical space of the exhibit, annotating the walls, stairs, railings, elevators, and corners. Next to the stairs leading up to the main space of the exhibit was a note in typed print requesting, “Please do not climb or sit on the stairs.” Below the classic instruction, written in messy handwriting between parenthesis was, “you may Look DuMB.” And the exhibit attempts to capture this sense of personality and subjectivity with which each individual mind approaches the world, formulating constant mental commentary while navigating through life.

A flier in the lobby of the ICA informed me that Happy Show was on the second floor of the institute. As I climbed the steps I realize that there were words painted across the indent of the steps. When I reached the top and looked down I could make out the complete affirmation across the steps, “PEOPLE TO CHANGE.” The exhibit subtly revealed its goal; it set out to change the way viewers think about happiness. Sketched along the railing was a message recording that the ancient Indian language Sanskrit contains sixteen words happiness while German includes none. Sagmeister asks, “Does this mean that Indians are happier? Or do they just know how to talk about it properly?” These two antithetical nuanced language differences embody divergent approaches to the inadequacy of language. Sanskrit grasps at an almost endless list of words, each failing to fully express happiness precisely, while German simply doesn’t try. Sagmeister enters the same quagmire, but he arms himself with tools beyond language. He admits, “I am usually rather bored with definitions,” but happiness is the “one thing we all want but never seem to be able to get for very long.” So he tries to pinpoint it through an interactive exhibit that works on all of the senses.

The exhibit manages to interweave a sense of familiarity with clinical psychoanalysis. The first quote leading up the stairs to the exhibit informs, “Research psychologist Jonathan Haidt describes the mind as a small rider, the conscious, sitting on a giant elephant, the unconscious. The rider thinks he is in charge and can the elephant where to go, but the elephant has his own ideas.” And the exhibit is a mental ride. I felt my own mind riding along Sagmeister’s as I made my way through the designs. Before entering the exhibit I was asked to draw my own symbol of happiness on an index card with a sharpie. The collective explanations of happiness offered by the visitors are recorded online. I drew two hands intertwined within a heart. Others drew pictures of a homemade bacon and eggs breakfast, a piece of cake with the inscription, “cake makes me happy, for four minutes,” and a graph with a life represented by a wavy line between the axis happy and sad, among others. Before entering the main section, I faced a large picture frame. Written beneath it was, “Smile.” I put my face through the frame and as I smiled widely words began to rise and light up from the floor in front of me until shining from the ground was the message, “Step Up To It.” It urged me to own my own happiness, to actively smile, to be happy.

The next design was a series of video screens. The first displayed an old woman’s naked and wrinkled body sitting cross-legged. Different shots of the woman displayed her body in different positions with words painted in black across her skin. The message spelled out “It’s pretty much,” across the top, “impossible” across her breasts, “to please” along her long legs, and “everybody” across her arms and chest. The next video screen recorded Sagmeister’s transformation of New York City. He went around to different familiar spots and changed them, if only slightly. In the window of a coffee shop he painted “used,” in a supermarket he wrote, “time,” with tuna cans, he wrote “taking” across the side of cop car. Then he wrote “IT” in honey across his chest and lied down in the summer street until bees covered his skin. Three of his friends swam across the Hudson river, spelling out “for” across their backs. These different alterations eventually wrote, “Over time I get used to everything and start taking it for granted,” all across New York City. Sagmeister’s designs challenge the status quo within society. He explains that he once saw a beautiful eighty-year old woman dressed in black on the subway. He felt the urge to tell her how beautiful she was, but he chickened out and she left the train at her stop. Suddenly he found himself racing off the train after her. “You are fantastic,” he told her. When she smiled, he promised himself that he would continue doing this in daily life, sharing his thoughts with those around him and creating simple connections with others. A small change he made to overcome his social anxiety was asking a woman holding a coffee cup where she bought her coffee rather than continuing aimlessly in search of a coffee shop. Why isn’t that normal?

The next screen displayed the message, “Having guts always works out for me.” “Having” was spelled out in white cloth in a forest through the trees, “guts” was written in furniture in a band’s garage practice space, “always” was written in a marker across white tulips that slowly wilted as the movie continued, “works out” was shaped by leaves piled up on an outdoor basketball court that blew away with a gust of wind, “for” was written in little cut up pieces of hotdog meat, and finally the camera moved through a party of dancing and chatting people before finding “me” spelled out in a tower of playing cards, lost and neglected in the corner of the room. Sagmeister understands social anxiety. He expresses it and articulates it on screen, slowly impressing his message in his viewer’s mind’s eye. As I watched the screen the background music played a soft melody. The lyrics of the song were “this empty space deep down inside makes me feel like I’ve been eaten alive.”

At the center of the exhibit is a platform with a bicycle on it. I climbed onto the bike and began to pedal. Before my eyes words slowly lit up, spelling out, “Actually doing the things I set out to do increases my satisfaction.” I had to pedal hard and diligently for the entire message to appear. I couldn’t give up. Then finally in bright read lights the final message appeared, demanding, “Seek discomfort.” A final message of the exhibit was, “Now is better.” This caption was spelled out in cups of overflowing coffee, eggs cracking and splattering, and milk sputtering from small containers. You can miss your chance in life.

Before entering the exhibit I came face to face with a disclaimer. “This exhibition will not make you happier. It will not take away your anxieties. If you regularly weep into your pillow at night, visiting the ICA won’t keep you from doing so. These pieces will not stop you from having dreadful thoughts during your morning shower.” No, the exhibit won’t solve your problems. But it just might give you a new perspective on your own emotions, it might break you free from your own mind for a few minutes, and it might help you realize that the world is not under your control but what you do and how you think can be changed at every moment. Find out for yourself.

– Erica Kimmel

The Happy Show. Through August 12, 2012. Institute of Contemporary Art, 118 S. 36th Street. Hours: Wednesday, 11am – 8pm, Thursday and Friday, 11am – 6pm, Saturday and Sunday, 11am – 5pm, Monday and Tuesday, closed.

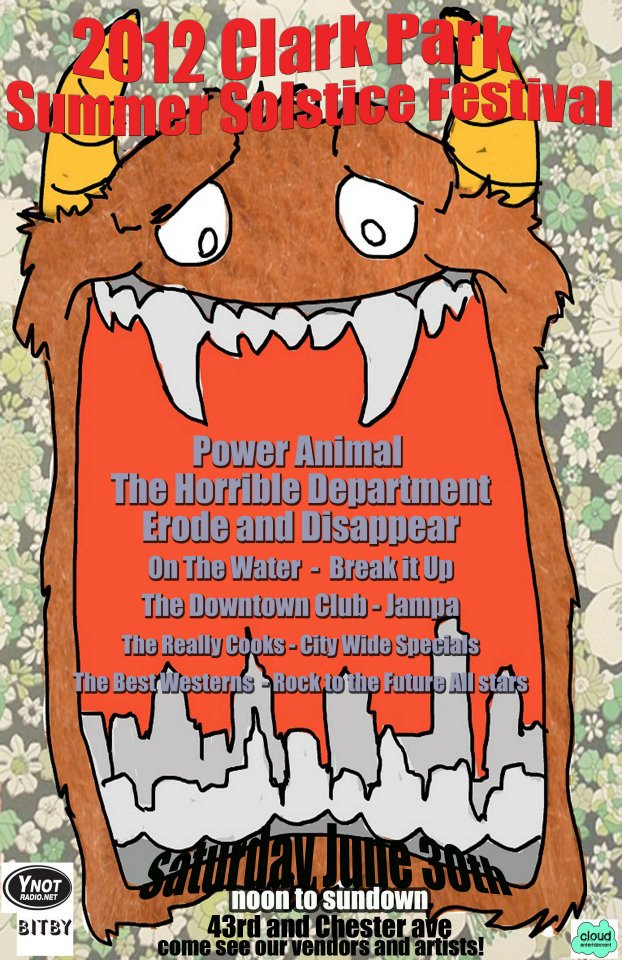

The festival runs from noon-8 p.m. Some of the bands featured this year include Power Animal, The Horrible Department, and the West Philly based City Wide Specials, among others. See below for a full list and set times. The forecast for this Saturday is mostly sunny with a high of 94, so make sure to pack a lot of sunscreen.

The festival runs from noon-8 p.m. Some of the bands featured this year include Power Animal, The Horrible Department, and the West Philly based City Wide Specials, among others. See below for a full list and set times. The forecast for this Saturday is mostly sunny with a high of 94, so make sure to pack a lot of sunscreen.

Recent Comments